D&AD Black Pencil Judging 2015: An insider’s view from The Glue Society’s Jonathan Kneebone

This year the D&AD judging took place in Shoreditch, London’s hottest suburb. And when I say hot, I actually mean it.

This year the D&AD judging took place in Shoreditch, London’s hottest suburb. And when I say hot, I actually mean it.

Unlike Sydney, the April weather in the UK was far balmier than usual. Which made the locals bare-armier and distinctly barmier than usual.

With the knock-on effect that checking in to the uber-trendy Ace Hotel reception – which appears to provide the entire local hipster community with free wi-fi as well as a place to park their rears and their fixed gears – was a virtual impossibility.

But that said, I can testify from experience that it was easier to get into your room at the hotel than into this year’s D&AD annual.

This is the first year I’ve witnessed the entire journey a piece of work has to take from its first showing in a dark category jury room on a Sunday morning to an even darker black pencil judging five days later.

This is the first year I’ve witnessed the entire journey a piece of work has to take from its first showing in a dark category jury room on a Sunday morning to an even darker black pencil judging five days later.

As a foreman (in my case Film Craft), I was invited to be part of the final panel beating that is the black pencil jury.

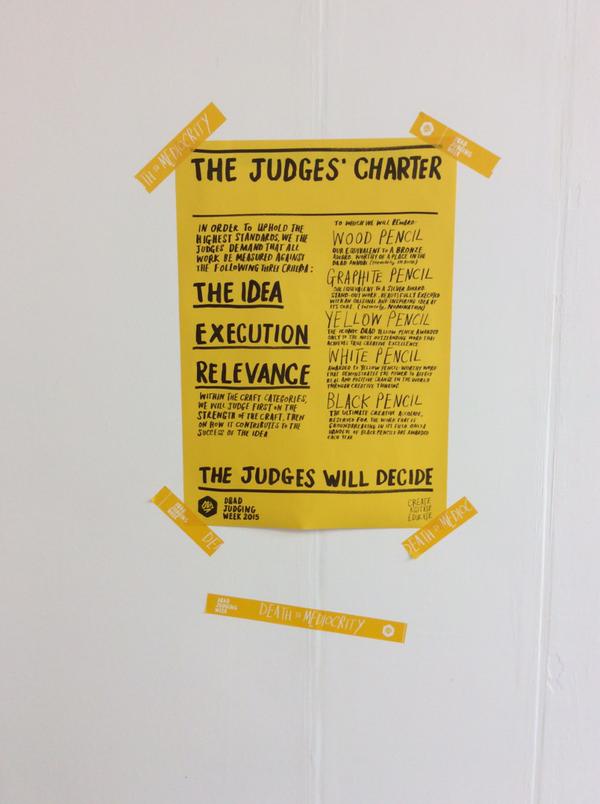

But to reach this stage, a piece of work first has to get into the book by a majority of votes (wood pencil). Then receive a nomination by a majority of votes (graphite pencil). Then receive a yellow or white pencil, by a majority of votes. Then receive a nomination for black pencil by any one of the foremen and women. And finally collect over 60% of this uber-jury’s votes to walk away with a top trophy.

This year, with 1158 entries, Film Craft was by far the biggest category. (I think the entire show stretched to over 15 times that.) And it took the ten of us three full days to watch everything, let alone reach a verdict on what was felt to be worthy of inclusion in the annual.

We found ourselves to be overly generous at this stage – with 107 pieces being recognised, across ten categories. Animation, Cinematography, Direction, Production Design, Use of Music etc. We wanted to reward a variety of approaches and styles.

But there the kindness ended. From this array we culled our first round candidates to just 28 nominations. And finally decimated the thousand entries to a few yellow pencils.

Things you might have thought would be a shoe-in walked away with nothing. And things which were exceptional for an ordinary ad break suffered by the comparison of being included in several hundred ad breaks back to back.

I think the fact that it is so especially hard to win anything at D&AD is part of its appeal and value within the creative community.

And I can only applaud the pieces of work and the people which were recognised with a yellow pencil.

To that end, this particular award show does have the additional benefit of tending to celebrate the creative inidividuals responsible for a piece of work as opposed to giving glory to the rampant and rather faceless networks.

The curse of the Gunn Report has totally re-engineered the purpose of most award festivals. And, rather depressingly, it has become about throwing money at multiple entries to amass points to climb ladders to impress global shareholders. Which feels very much at odds with celebrating creativity. And does rather create a false sense of which agencies can genuinely claim to be the best in the world.

Thankfully, D&AD – certainly in Film Craft – does actually award its pencils to the creative individuals who have done the work and deserve praise or recognition.

The directors, the editors, the animators and for the first time year the casting directors. And by giving people proper recognition, we come to recognise their names.

Which brings me back to the darkness of the black pencil jury room. And when I say dark, I mean literally and emotionally.

Because here, a few recognisable faces emerged to brilliantly illuminate the room. Eric Kallman, Ted Royer, PJ Pereira, Kate Stanners, Piyush Pandey, Steve Henry to name a few of the fourteen advertising judges.

From the shortlist of yellow pencil winners (in reality, the very short list), we debated which were worthy of discussion for black.

Which then set in motion a six and a half hour conversation, which at times got as heated as the weather. After which we voted in silent secrecy.

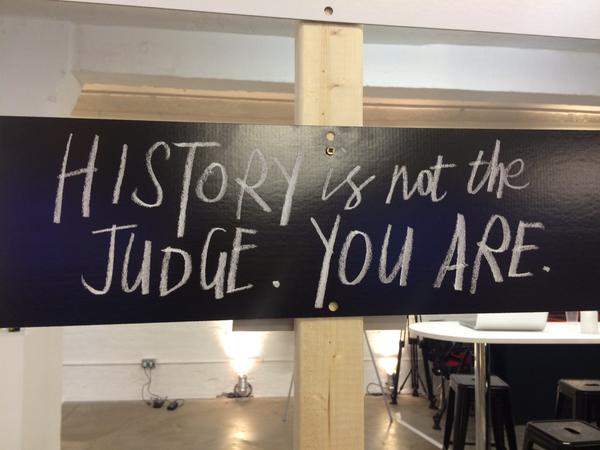

On May 21st, we will all find out just how few pieces of work, if indeed any, got sufficient votes to go down in history as this year’s black pencil winners.

On May 21st, we will all find out just how few pieces of work, if indeed any, got sufficient votes to go down in history as this year’s black pencil winners.

But there is one thing that I can tell you now.

The most significant out-take this year would be that doing work for brands which creates positive cultural change or challenges discrimination is now not just a nice-to-have – it’s a why-the-fuck-aren’t-you.

The white pencil award was introduced to recognise work and brands that are doing good. And as its category foreman Steve Henry very potently and passionately argued that this isn’t just about creating brave new communication it’s about reviving a dying industry.

During the festival too, Olivier Toscani hammered adland for being increasingly dull, irrelevant and easily ignored.

If we can use our ideas and wits then to encourage marketers to go beyond the self-fuelling money-grabbing behaviour for market share they are all comfortable with, and move them to a place where they are provoking positive change, then it actually might just make the advertising industry and agencies in particular more relevant and valued as partners in the process.

It might mean we are forcing brand managers to put their jobs and balls on the line by doing something which potentially upsets a few people to such an extent they stop buying their products.

But whether it’s tackling waste, fighting racism, promoting gender equality or using our creativity to kick-start social movements against corporations who don’t give a shit about just how shitty they make the world, the time for agencies and creative people within them to start having these tough conversations with clients is now.

Doing good won’t necessarily win you a black pencil. After all, as the now rather clichéd saying goes, good is the enemy of great.

But if you do good and don’t get in the DA&D annual, you can still say you’ve done something worthwhile.

You might even earn the respect of people who don’t work in the advertising industry. Which perhaps is rather more rewarding.